One of the most cherished ideals of the West and its glorification of its parliamentary and representative democracies is freedom of speech. And yet in practice, free speech really isn’t free. If you are rich and white, male and heterosexual, your wealth and power provides you free speech in ways anyone who cannot check off all four categories can only hope to imagine. Heck, given how frequently powerful white men denigrate entire classes of marginalized people with impunity and without consequence, it seems that free speech was only meant for certain people. Apparently, free speech for the rich and powerful (especially white men) is really the right to be toxic, narcissistic assholes whose brains — especially the parts that control higher-order thinking and empathy — stopped growing sometime around puberty. In a post-Western world, this ill-defined right will receive a full-revisit and a radical reset.

“We are so pleased to announce that the United Nations’ Select Subcommittee on the Human Right of Freedom of Speech and Expression, as part of the UN Second Declaration of Human Rights Convention, has concluded. On this day, Wednesday, 23 September 2189, our Select Subcommittee has created a document based on one simple idea. This freedom of speech, this right for individuals to express their individuality, is only free so long as individuals do not weaponize it in the desecration and destruction of other individuals and of other communities. No one individual exists in hermetic isolation. No one individual should have wealth or power sufficient to use their words and their deeds to oppress or rally numerous others for the goal of oppression and genocide.”

So said Bibi Montsho, a lawyer and a linguist from the Southern Cone, the head of the 20-person subcommittee. As she moved her burgundy brown braids off her face, she took a moment to look around the half-full, 340-person auditorium on the Universidad de São Paulo campus. This was among the first steps toward the big moment, two months into a three-year-long divorce process from the Western global order. Bibi’s lustrous skin glowed like a warm brown star that day, thinking of how the news of her subcommittee’s work would hit about this announcement.

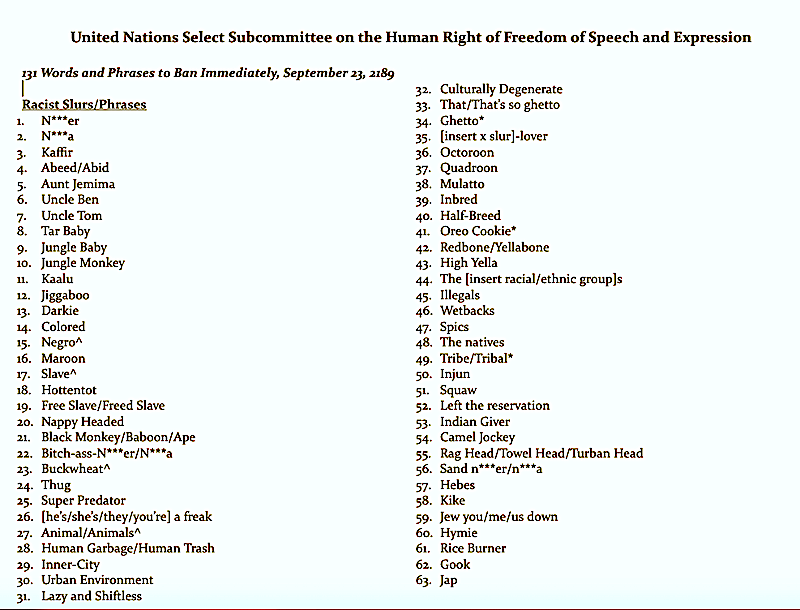

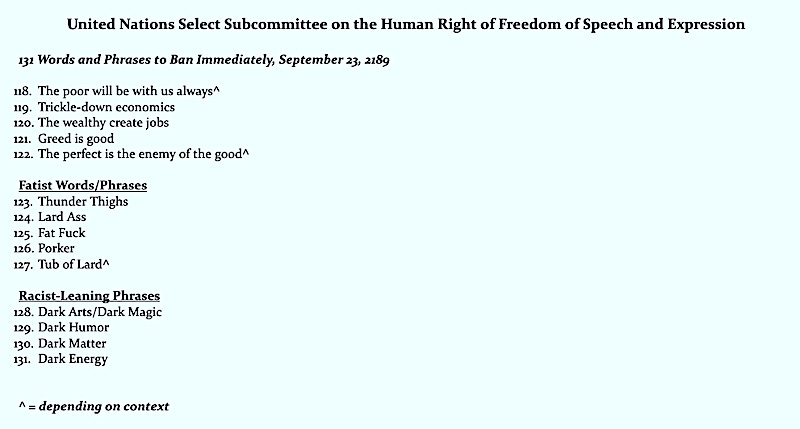

The announcement on 23 September 2189 was that the Special Subcommittee had created a list of 131 commonly used words, phrases, and sentences to ban from public discourse. Starting with the n-word, the subcommittee had worked its way through more than 3,000 global expressions that ultimately could denounce, dehumanize, and incite populations of racist, sexist, queerphobic, and xenophobic people to exploit, abuse, enslave, and murder their human neighbors. Like everyone else in the room, Bibi understood that banning such words “would not do away with human cruelty or end the tendency among humans to elevate oneself at the expense of all others.” “But,” as Bibi so eloquently put, “it’s a helluva start. We cannot have a new world order with the old world’s words.”

As part of this first round of revisions to the original UN Declaration of Human Rights, committees and subcommittees were to carry out the charge of “fleshing out as many dimensions of human rights as possible, but with a balance between individuality — not individualism — and communal purpose — not mindless collectivism.” The Select Subcommittee saw theirs as a simple task. They were to answer the question: Are there limits to freedom of speech and freedom of expression, and if so, what are those limits?

Yet the answer was complicated. Everyone on the subcommittee agreed that speech and expression that dehumanized entire classes of people was completely out of bounds, whether Black folk, Queer folk, Indigenous folk, women folk, disabled folk, or elderly folk. The problem was, two of the 20 members — one from the former United States, one from the soon-to-be dissolved United Kingdom — refused the idea of limiting free speech and free expression in any way.

One of them, Marjorie Kelly-Rappaport, whose family survived the former US’ Second Civil War and the Nuclear Winter of 2074-2083, represented the Dissolved Nations of the Western Hemisphere consulate in São Paulo. Despite the road of perdition racist demagogues had taken the former US down in the century before its violent collapse, Marjorie was stiff-necked on the issue. “I cannot believe you people! Unlike most of you, I have relatives who still feel the pain of my country’s demise. Even with America’s flaws, we still had the most freedom of any country in the history of the world. Our constitution was the most righteous. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech,” she said with her voice rising. “That was our First Amendment!” Marjorie’s crocodile tears streamed down her freckled cheeks and smeared her charcoal mascara.

A couple of the men in the room seemed swayed by Marjorie’s appeal. But not Bibi. She barely controlled her urge to roll her eyes, but did shoot a look at Sade Wamuniga-Chisholm, her other Southern Cone colleague, who gave her a quick and subtle head shake. Then, she started in on Marjorie.

“Ms. Kelly-Rappaport, no one here wants to trample the human right to protest, to speak one’s mind, to say something meaningful or meaningless to the world through art, music, dance, writing, athletics, or by just existing as their full selves in this world. But why do you think this right gives anyone the right to threaten and dehumanize millions of people? Even now, in 2189, your country has existed for a century, and yet you have the audacity to say ‘you people’ in a way that treats the rest of us as inferior. Brazil, the Southern Cone, and the Ghana-Nigerian Zone host 60 million descendants of your beloved dead country. Be glad that we have yet to discuss what the penalties should be for your narcissistic need to abuse others.”

“I didn’t mean anything by it,” Marjorie said with a pout. Two members of the committee murmured “Pinkskin” while Marjorie issued her mea culpa.

“As we have already discussed for the past six weeks, your intent is of no consequence. The harm is what really matters,” Sade said.

“For your benefit and the benefit of the subcommittee, I will reiterate what I said on day one. It is ironic that in the years after the Second World War, the US forced Germany and Japan to rewrite their constitutions. Their language and balance between rights and responsibilities for such rights is undeniably better than in the US Constitution. It should be clear to anyone that freedom of speech has to be in balance with the needs of humanity as a whole. No individual should ever be so into themselves that they forget the needs of the human community.”

On their screens, Bibi put up three quotes.

“Where in this language, pray tell, does it say every human has the right to abuse, dehumanize, and otherwise oppress others, through speech and expression? Where does it say that every human has the right to use speech and expression to incite other human beings to oppress, abuse, and murder?,” Bibi rhetorically asked.

Marjorie remained pouty and silent, her arms folder, her chin firmly pinned to her chest.

Then Dr. Eric Nchami spoke. He was a professor of cultural linguistics from the Ghana-Nigerian Zone. “It seems to me that we should continue on the path that our distinguished colleague Ms. Montsho has set us on. We need to say with one voice that some words and phrases are just too anti-humanity to be used in public discourse, in private settings, really, anywhere. Why do we need to retrace the steps of a dead empire? Why should we repeat the mistakes that cost the world billions of lives and millions of species.”

Sade clapped, followed by Bibi, then Eric and the others. Marjorie decided after that day to resign from the subcommittee, but not before filing a formal complaint. “If people do not have the right to say what they think, there is no freedom of speech. We can’t ban all the hurtful words.”

The subcommittee never tried to ban words that hurt people’s feelings. What they did do, though, was recommend that the use of certain words and phrases, depending on context, simply needed to be prohibited in public discourse. Some words were poisonous in every context, even when oppressed people attempted to use such words as positives. Other words and phrases had specific contexts that could do damage and dehumanize others as individuals, while other words and phrases were meant to abuse specific groups. All the ones the subcommittee agreed to were ones that individuals in the West had either spread to the world or were ones that the West made worse by imbuing in such words the ideas that some humans were inferior to others.

Maybe this should have been controversial. But with nearly seven billion people and 30 percent of all life on the planet dead after 150 years of civil wars, nuclear exchanges, and rising sea levels, the surviving world welcomed the end of Western narcissism. There is something to be said about not trashing entire groups of humans for the sake of one’s need to elevate themselves.